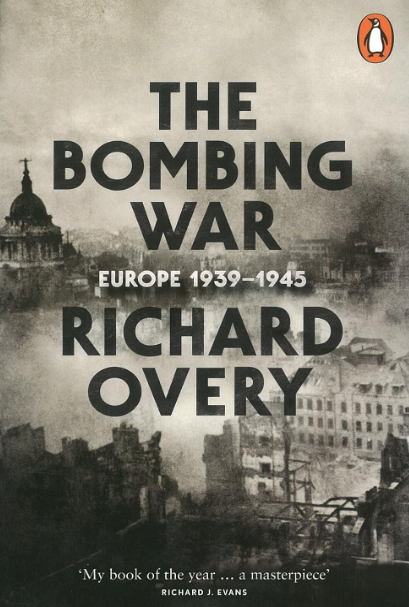

Thread on the WWII aerial bombing campaigns. Main sources throughout will be Richard Overy’s authoritative history, “The Bombing War: Europe 1939-1945” (2013) and earlier work "The Air War: 1939-1945" (1980), as well as his online lectures on the subject. 1/

Like anything else in the study of history, context is everything. As we saw e.g. with Pearl Harbor, to understand the decisions of military planners we must know the information available at the time and their key operating assumptions. 2/

1932 - Adm. Schofield, Pacific Fleet Commander, predicts that at the outset of a war Japan would cross the remote “vacant sea” to attack Oahu from the north (exactly what they did).

— Lunkhead (@Antweegonus) May 29, 2023

War games through ‘41 are designed on this basis, which include use of carrier-based planes.

15/ pic.twitter.com/Blae6wSkTw

In the interwar period, urban Europeans were terrified of the prospect of area bombing. The common view was that cities in the next war would be reduced to ash almost immediately, similar to the view people came to have of nuclear weapons just a few years later. 3/

Interwar efforts to forbid aerial bombing of civilian targets under international law fell short. Heavy bombers were seen as a useful strategic asset, and European powers were reluctant to bind themselves with self-imposed limits on their use. 4/

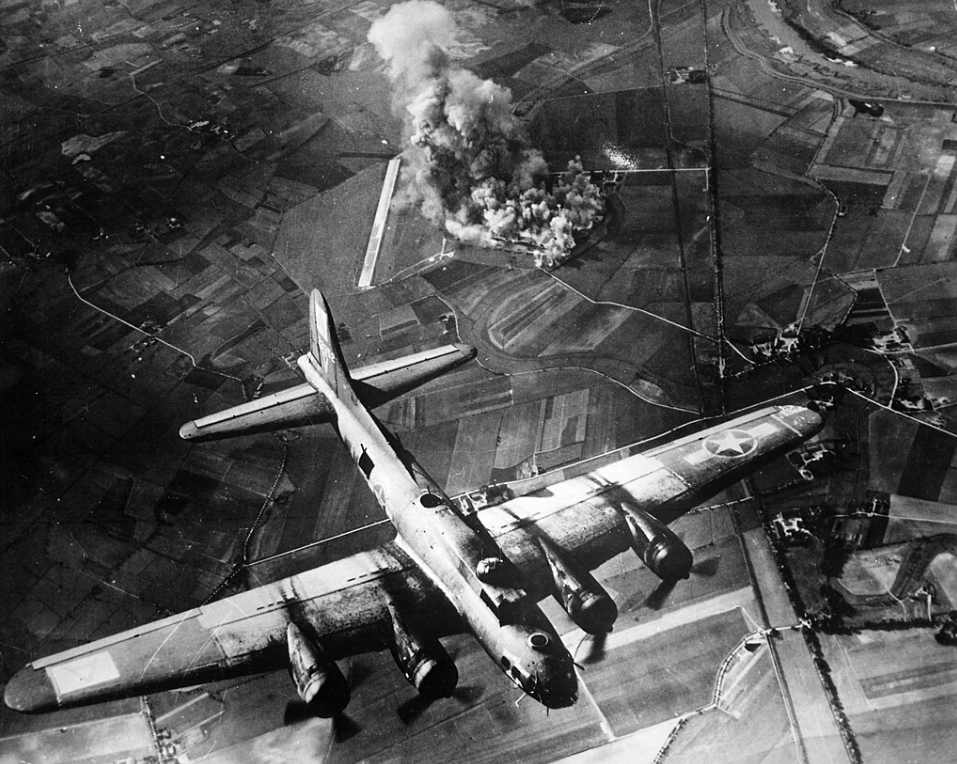

Some British planners believed aerial bombing would be a fast and cheap way to achieve two objectives: 1. Disrupt the enemy’s economy via destruction of industry 2. Weaken enemy morale by targeting civilians, with a possible political dividend of regime instability/collapse 5/

But there was no clear evidence aerial bombing was effective at achieving either of these. Most European countries concluded after the Spanish Civil War that aerial bombing was much more effective when used in combined arms operations, as opposed to independent air campaigns. 6/

But Britain, alone among European powers, made heavy bombers a central part of its war plan. Churchill was a major advocate of bombing civilian targets and said so repeatedly from at least 1920 onward. 7/

In July 1940, he wrote: “There is one thing that will bring [Hitler] back and bring him down, and that is an absolutely devastating, exterminating attack by very heavy bombers from this country upon the Nazi homeland.” 8/

Roosevelt shared Churchill’s view, despite his initial formal appeal in September 1939 for both countries to avoid aerial targeting of civilians (to which both agreed). 9/

RAF Bomber Command’s approach was based on its experience suppressing colonial uprisings, where long distances and poor communication made deployment of ground troops difficult. A few bomb runs often proved effective at forcing tribal enclaves to surrender. 10/

Bomber Command believed the same tactic could be applied at scale to achieve the same result against civilized European nations. They were mistaken, as both the British and German peoples proved time and again. 11/

The German Blitz of 1941-42 also made it clear that even delibrate destruction of industry was ineffective at causing serious economic disruption, having only reduced the British economy by ~5%. All of this was known to the RAF by late 1941 and discussed by the Air Ministry. 12/

So the British needed an additional justification for aerial bombing, which was that they believed the German populace was simply not as tough, lacked the "moral fibre" of the Brits and would fold under pressure where they didn’t. They were, again, mistaken. 13/

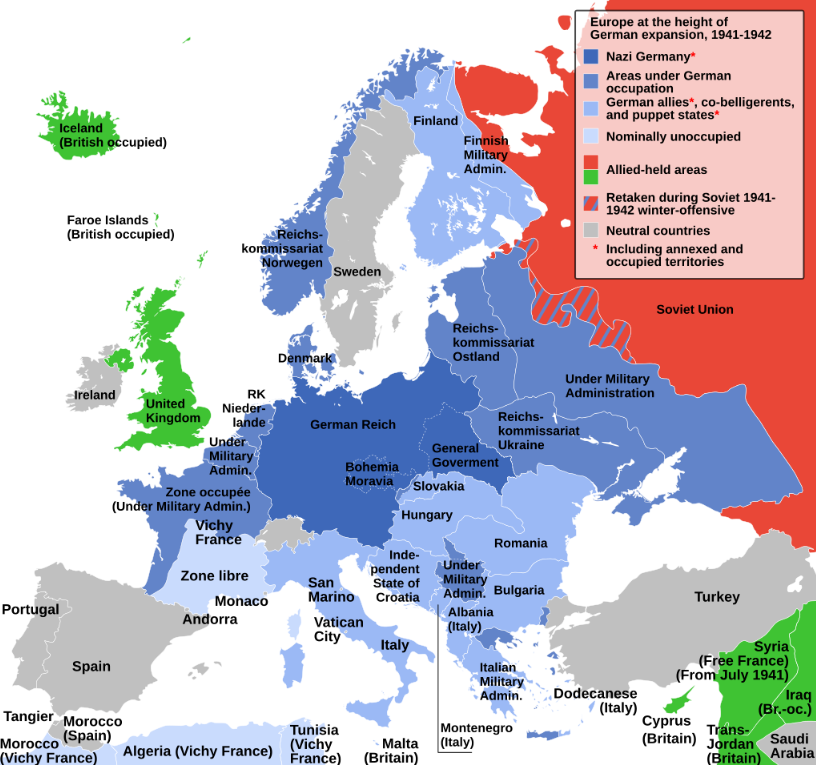

Hitler, in contrast, especially after the relative ineffectiveness of the Blitz, was deeply skeptical of the military utility of aerial bombing, favoring maneuver-based combined arms doctrine (e.g. Blitzkrieg). 14/

He often complained of the Luftwaffe's inaccuracy and inability to meaningfully damage homeland economies: "The munitions industry cannot be impeded effectively by air raids . . . usually, the prescribed targets are not hit." 15/

In planning the war he never ordered the Luftwaffe to formulate strategic bombing campaigns at all—though he did employ the threat of it to force diplomatic submission of smaller nations in the 1930s (perhaps taking a page from Churchill's "colonial policing" book). 16/

Now, the timeline. Overy traces the start of the bombing war to 10 May 1940, the day Churchill replaced Chamberlain as Prime Minister (who, unlike his successor, always opposed the bombing of urban targets). 17/

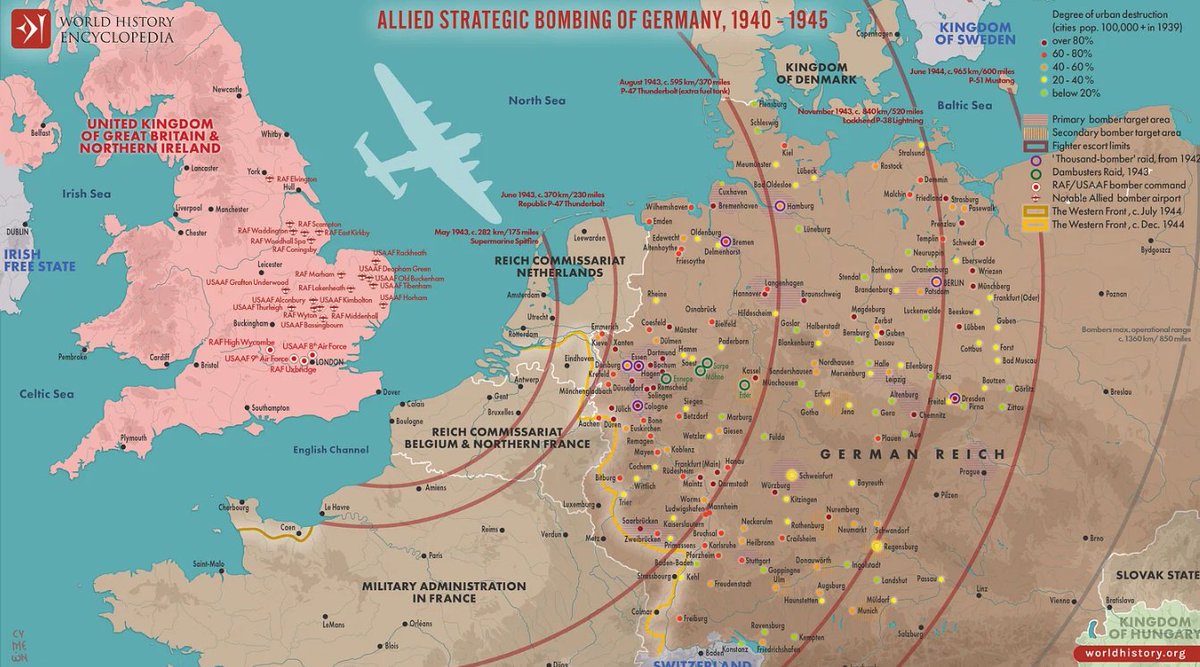

In the following days, in response to the German attack on Rotterdam, the RAF bombed the German town of Moenchengladbach, civilian oil installations in Gelsenkirchen, Hamburg and Bremen, and railway yards in Cologne. 18/

Later in May: Essen, Duisburg, Düsseldorf, and Hanover in similar fashion. In June: Dortmund, Mannheim, Frankfurt, and Bochum. Germany first began aerial bombing of Britain in mid July, after nearly two months of British bombings of German cities. 19/

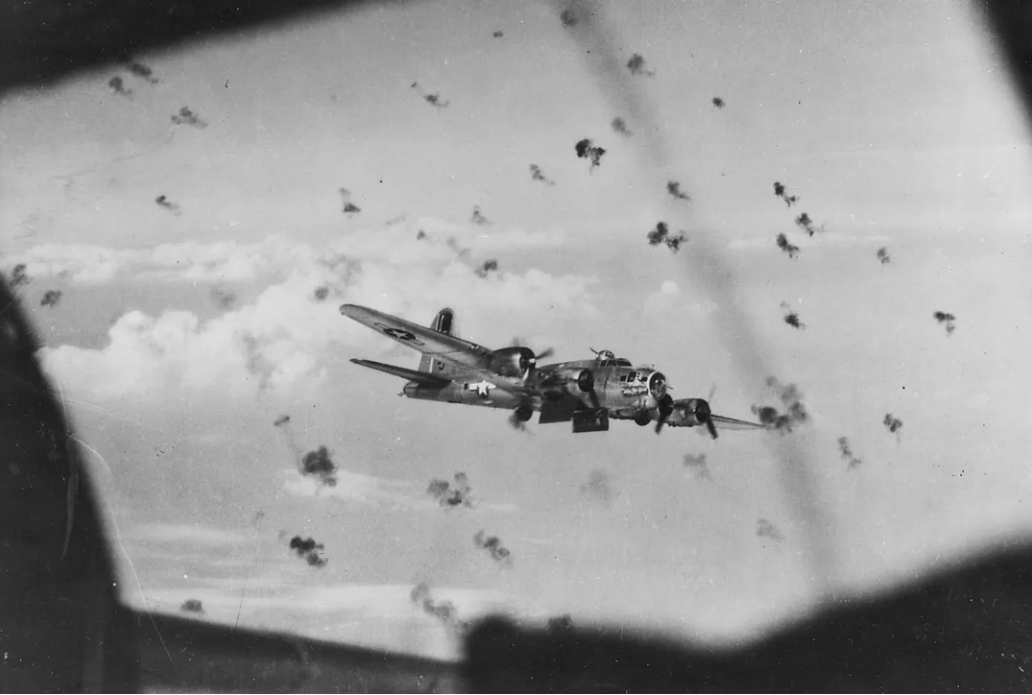

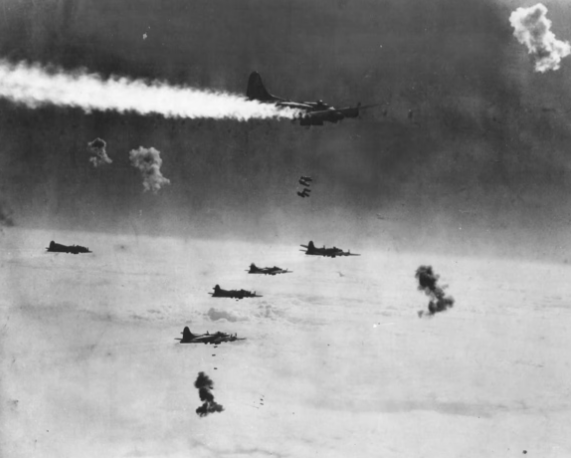

It should be noted that at this point, both countries Air Ministries’ were officially limiting aerial bombings to military and industrial targets. The problem for the British was that German daytime air defense was too effective, and the RAF was losing too many pilots. 20/

So they started bombing at night. The problem with bombing at night was that precision strikes became nearly impossible, and bombings became so inaccurate that civilian areas were often hit anyway, causing widespread uproar throughout Germany in May-July. 21/

Its also why in 1941, the standing guidance to Bomber Command was amended such that they intent of the bombings was no longer to cripple German industry, but German morale via indiscriminate bombing of the civilian population. 22/

That isn’t to say the OKL (German Air Ministry) had clean hands. Their bombings of Warsaw in '39 and Rotterdam in '40 were at least grossly negligent in their destruction of civilian areas—and of course, the later Blitz, which killed some 20-40,000 civilians in London. 23/

Brief aside: it should be noted that Hitler never actually wanted war with Britain or France, and was surprised at their declarations of war in September 1939. 24/

He sued for peace several times, offering to withdraw from France, Belgium, Norway, and the Netherlands, while retaining Luxembourg and German-speaking Alsace-Lorraine, and with the agreement of Britain to not intervene in their war with the Soviets. 25/

Obviously, it’s debatable whether it would’ve been wise at the time to trust Hitler to abide by such terms, especially considering his failure to do so after the Munich agreement of 1938. 26/

It’s also worth noting that Britain’s chief foreign policy aim, as in the Napoleonic wars, Crimea, & WWI, was to prevent the emergence of a continental power to rival Britain, especially at sea. Again it's impossible to understand this war without grand geopolitical context. 27/

Back to the bombing war: the Luftwaffe accidentally bombed a civilian area of London in August 1940, which spurred Churchill to bomb Berlin days later. Hitler, not knowing of the first bombing, ordered a retaliatory bombing of London on 6 September, just before the Blitz. 28/

Contrary to the belief firmly rooted in the British mind since 1941 that Hitler began the trend of indiscriminate bombing, Overy makes it clear that it was Churchill who decided to 'take the gloves off'--not in response to German raids, but to assist in the Battle of France. 29/

Churchill himself did not view his air campaign against Germany as retaliatory or defensive, but in his own words, as "pre-emptive retaliation" for crimes he expected the Germans might commit in the future. 30/

The bombing war continued into 1942, though the German air effort against Britain mostly petered out after the Blitz ended in late 1941, with most of the Luftwaffe sent east against the Soviets. 31/